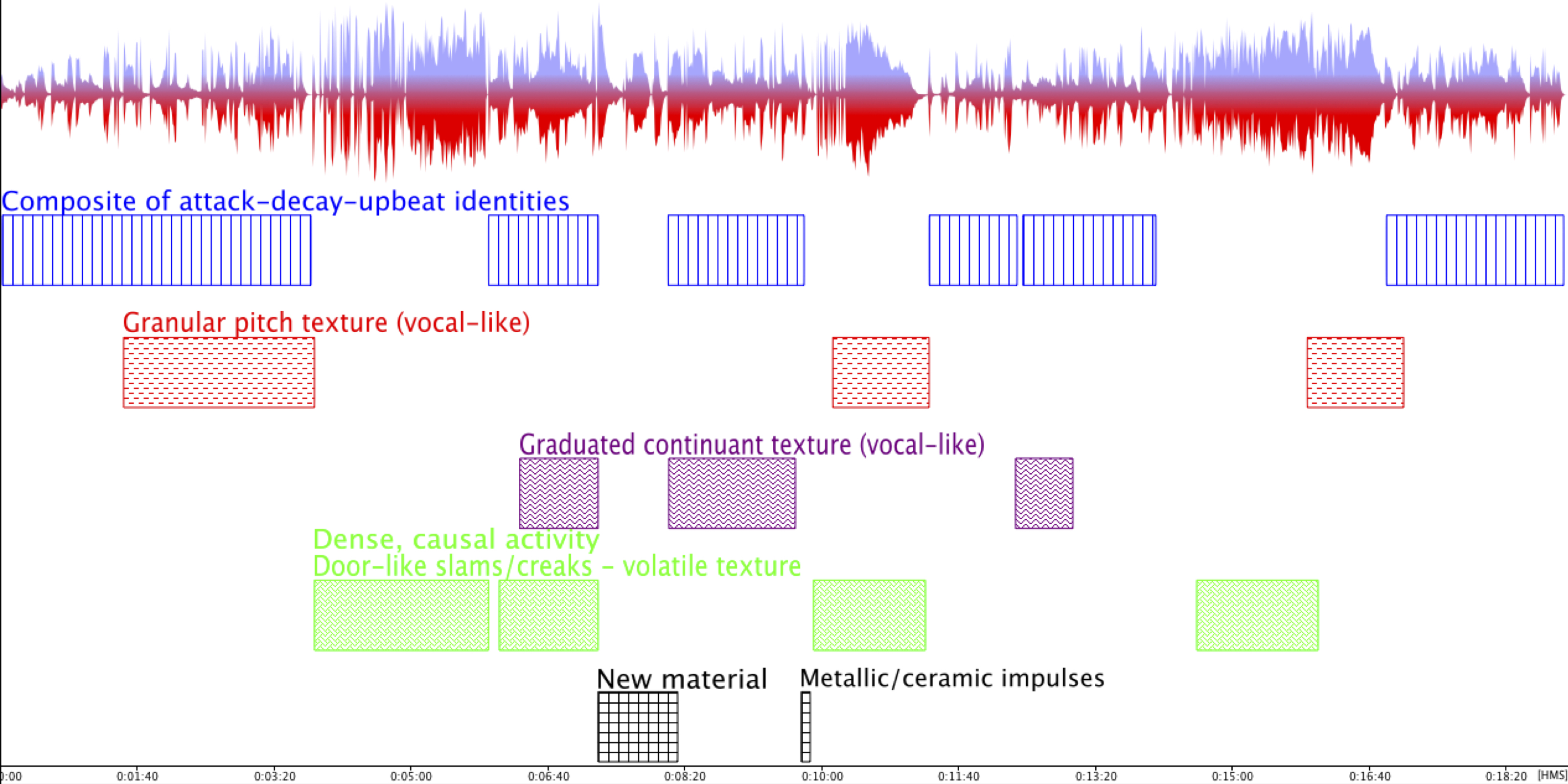

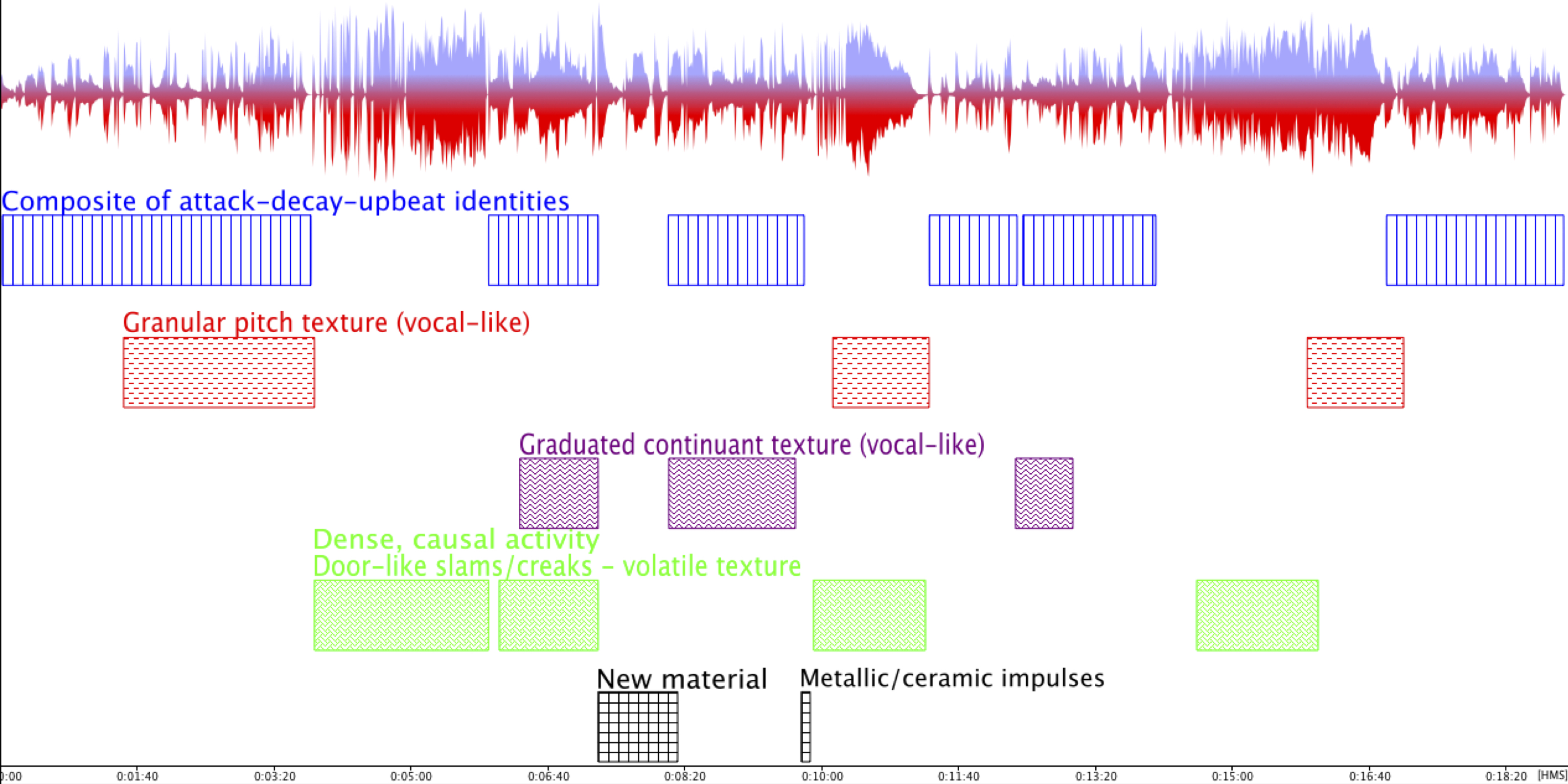

Novars opens with a striking composite of pitch-based, attack-decay-upbeat identities. After the initial discussion of this composite of identities (which can be considered an identity in itself), higher-level relationships among its recurrences will be appraised, followed by a discussion of the two other significant recurrent identity types: volatile textural material based on door-like slams and creaks, and granular pitch textures that exhibit vocal-like spectral content. Lewis’s analysis of this work includes a structural diagram that illustrates where the main identity types recur [1]. For this discussion, a similar but simpler diagram is provided, focusing on the occurrences of the main identities (Figure 2). Whilst some of the identity descriptions used in this article are similar to Lewis’s (e.g. door-like slams/creaks), they often differ slightly in order to highlight the distinguishing spectromorphological features appropriate to this discussion.

Figure 2: Overview of Novars.

The opening of Dhomont’s Novars [2] features attack-decay morphologies in a variety of orientations.

Sound Example 1. Dhomont, Novars, 0’00–1’40.

A variety of forward and reverse versions exhibit different kinds of prolongation while also creating occasional upbeats; distinct sound shapes are easily discernible. The identities of the weakly source-bonded opening instances are defined and united by gestural impetus, morphological profile, and a pitch content that is primarily stable. Pitch stability lends the passage a sense of permanence, yet the attack-decay morphologies also exhibit spectral contours, which manifest as progressive high-frequency restriction or sudden spectral brightening. All these features contribute to the gist of these identities. Lewis has described these as “Filter-Swept Chords/Resonances” in his analysis of this work [3], and the occasionally unexpected nature of the ‘filter-sweeps’ further characterise the identity. High-frequency restriction often coincides with the decay of the sound, as might be expected in real-world decay phenomena (although here it is exaggerated), but occasionally the reverse-attack morphologies feature similar progressive high-frequency restriction. This subverts any sense of realism and further characterises the sound material. According to Smalley’s concepts of gestural surrogacy, these identities can be considered third-order, tending to remote, gestural surrogates [4]; listening tends to focus on the sudden gestural action, and how the spectra progress over time in both predictable and less predictable ways.

The linear arrangement of the attack-decay morphologies, combined with the subtle changes in spectral content, focuses attention on the progression from one instance to another. The strength of identity of this sound material is reinforced by its temporal organisation, and the play on permanence (pitch) and variation (gesturally and spectrally) is a significant aspect of the passage. There is an intrinsic connection among forward-attack and reverse-attack morphological types (a form of ‘source bonding’), their arrangement here suggesting an organisational process evolving from the opening attack morphology. This, coupled with the general pitch stability, creates a sense of cohesion within the sound world. Indeed, a sense of cause-and-effect exists between each attack-decay structure, and the sound material can be viewed as a series of morphological events that contribute to the perception of a longer, composite identity.

This composite chain of attack-decay-upbeat identities [5] initially occurs on its own.

Sound Example 1. Dhomont, Novars, 0’00–1’40.

Subsequent recurrences establish higher-level relationships throughout the piece while fulfilling characteristic structural functions within the immediate contexts. Shift or rupture functions occur most commonly, while the behavioural relationships [6] among the identities further define the recurrences in terms of relative dominance and degrees of coexistence.

The granular pitch texture then emerges from 1’30, eventually coexisting with the chain of attack-decay-upbeat identities.

Sound Example 2. Dhomont, Novars, 1’30–3’49.

The next passage features a contrasting acousmatic image of dense causal activity and volatility (3’49–5’57) dominated by the door-like slam/creak identities, building to a climax at 5’55. This passage features: noise-based (door-like slam source bonding) and inharmonic impulses (metallic and ceramic source bondings) with varying pitch emphasis and developing rhythmic phrases; creak-like pitch descents; and metallic, decelerating iterated impulses (entering at 5’25).

Sound Example 3. Dhomont, Novars, 3’49–5’57.

The opening chain of attack-decay-upbeats then recurs seemingly identically at 5’57, reinforcing this composite identity in consciousness as well as establishing a marker relationship, projecting back to the beginning and creating a sense of temporal perspective. This recurrence is striking because it contrasts spectromorphologically with the preceding material, characterising the spatial shift that consequently occurs. This shift is emphasised by the energetic accumulation of the preceding texture and by the energy dispersion conveyed by the returning chain of attack-decay-upbeats. (This could also be considered a ‘tension/(delayed) release’ function pattern; the activity must end at some point, and this end is confirmed by the recurrence of the opening material.) However, continuing elements of the volatile door-like slam/creak texture, along with the subsequent pitched, quasi-vocal graduated continuant morphologies emerging at 6’19, thwart any expectation of a complete return to the opening. So, although briefly dominant, the recurrent chain of attack-decay-upbeats soon coexists with the other elements in the acousmatic image.

Sound Example 4. Dhomont, Novars, 5’50–7’17.

Lewis’s diagram and analysis categorises the vocal-like, graduated continuant texture as the same sound type as the granular pitch material first emerging at 1’30. However, the morphological contrast is sufficiently strong to justify viewing them as distinct identities that exhibit a spectral covert correspondence. Therefore the purple regions commencing at 6’19, 8’08 and 12’22 are considered an additional sound type in this discussion, and have been distinguished in terms of colour and shading accordingly.

A rupture to predominantly new material (impacts of variable pitch, pitch sustains, glissandi and noise-based and pitch-based granular textures in proximate space) occurs at 7’15, and the three main identities are absent.

Sound Example 5. Dhomont, Novars, 7’10–8’07.

However, at 8’08 the second recurrence of the chain of attack-decay-upbeat identities ruptures this new territory. In addition to reinforcing the spectromorphological imprint and shift/rupture function, and extending the marker relationship, the initial attack instigates a recurrence of the quasi-vocal graduated continuants of 6’19 at 8’08 (although with different pitch focus). This additional functionality expands the role of the recurrence while connecting to the previous shift/rupture instance at 5’57. The recurrences of the chain of attack-decay-upbeats keep it in consciousness, increasingly suggesting that this material is never ‘far away’. As before, the recurrent material soon exists within a larger texture, but now features slight variation through transposition.

Sound Example 6. Dhomont, Novars, 8’00–8’35.

At 11’19, the chain of attack-decay-upbeat identities recurs a third time, momentarily in proximate space. The preceding granular pitch texture has dissipated (occurring at 10’05–11’18), and although there is a shift in setting, the onset of the attack-decay-upbeat morphologies is less striking than before because it does not appear to actively rupture or terminate the previous material.

Sound Example 7. Dhomont, Novars, 11’05–12’03.

Additionally, the chain of attack-decay-upbeat identities now features a higher frame of registral focus with changing pitch material, and the compromised spectral correspondence with earlier instances weakens the marker relationship, resulting in a more covert correspondence. However, this makes the next recurrence at 12’27 more striking. Spectrally the return at 12’27 corresponds more closely with the original version, and accordingly connects to it despite the distal location and more coexistent relationship with the other identities present.

Sound Example 8. Dhomont, Novars, 12’24–12’50.

The final recurrence, at 16’53, again follows the emergent granular pitch texture, yet appears before that texture has fully receded, deflecting away from the termination process. This heightens the impact of the recurrence and strengthens its marker relationship with the earlier instances.

Sound Example 9. Dhomont, Novars, 16’42–17’29.

Thus, throughout the work recurrences of this chain of attack-decay-upbeat identities are largely spectromorphologically consistent, exhibiting marker and reinforcement relationships to earlier instances. The chain of attack-decay-upbeat identities remains central to the music because its regular recurrences are a striking feature against which the evolution of the piece can be appraised. Its role is elaborated in relation to the other concurrent materials (also altering their significance) through its changing structural function and behavioural relationships.

The passage of rhythmic door-like slams/creaks at 3’49 recurs and is reinforced at 9’54. Both of these instances result from a shift, but from different contexts. The first instance at 3’49 shifts from the chain of attack-decay-upbeats coexisting with the granular pitch texture.

Sound Example 10. Dhomont, Novars, 3’30–4’09.

The second instance (9’54) also shifts from the chain of attack-decay-upbeat morphologies, but now alongside disappearing quasi-vocal graduated continuants.

Sound Example 11. Dhomont, Novars, 9’30–11’18.

Additionally, this later shift is instigated by iterative inharmonic impulses at 9’45 (possible metallic/ceramic origin), which rupture the existing texture (0’15 in the extract). The similar spectromorphology and shift function of the recurrent door-like slam/creak texture creates a marker relationship whilst elaborating on the original by reinforcing and developing rhythmic figures. The granular pitch texture (first heard at 1’30) then recurs at 10’00–11’18 alongside the door-like slams. This reinforces the granular pitch texture identity, yet in this instance it gradually dominates the acousmatic image. These two recurrent identities thus create a new context, combining and recalling two previously separate settings, while also providing a new perspective on each identity due to their redefined behavioural relationships. The emergent granular pitch texture now becomes dominant (at 1’30, it emerged to become coexistent), while the door-like slams gradually become subordinate and immersed, rather than building to a climax.

At 14’10 the rhythmic door-like slam identities recur, shifting from and rupturing the preceding chain of attack-decay-upbeat morphologies.

Sound Example 12. Dhomont, Novars, 13’53–14’31.

The spectromorphological correspondence and similar structural function of the rhythmic door-like slams maintains the marker relationship with those at 9’54, while reinforcing their rhythmic aspects. Although additional identities are present, the rhythmic door-like slams remain a dominant feature, characterising the section. The emergent granular pitch texture reappears by 15’57, reinforcing the two earlier instances (1’30 and 9’54) due to its spectromorphological and functional similarity.

Sound Example 13. Dhomont, Novars, 15’45–16’40.

Notably, both of the passages spanning 9’54–14’10 and 14’10–19’05 feature the door-like slams at the onset, then the emergent granular pitch texture, and terminate with the returning chain of attack-decay identities. This results in a recurrent sound-event chain, but latterly of slower progression.

Further covert correspondences are present. In his analysis, Lewis points out that the final passage features untreated sections of material from the first movement of Pierre Schaeffer’s Étude aux objets, as well as a cadence from Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame [7]. For listeners familiar with these works, these quotations may provoke impressions of retrospective significance and covert correspondence with the composite of attack-decay-upbeat identities and the granular pitch texture, alluding to their potential origin. For listeners unfamiliar with these works, the quoted material could solely be the source of a covert correspondence.

Sound Example 14. Dhomont, Novars, 16’50–19’05.

[1] LEWIS, Andrew, "Francis Dhomont's Novars", Journal of New Music Research, vol. 27, n°1-2, 1998, p. 71.

[2] DHOMONT, Francis, "Novars", Les dérives du signe, CD, Empreintes Digitales, 1989, IMED 9608.

[3] LEWIS, Andrew, op. cit., p. 69. Lewis further asserts that the pitch structure of the resonant sounds is based on “a quasi-fundamental, above which float other ‘partials’ based on a modal arrangement” and that, on occasion, this harmonic pitch set is disturbed by resonances foreign to the modal scheme (Ibid.).

[4] Smalley suggests that sound-making gestures (whether of human, animal or environmental origin) can be seen to create spectromorphologies. Conversely, any perceived spectromorphologies may be indicative of specific gestural events, which are identifiable to varying degrees of accuracy. Thus, the degree of perceived connection between a spectromorphology and its gestural origin can be described in terms of its gestural surrogacy. The categories are: first-order surrogacy (sound-making prior to musical organisation); second-order surrogacy (traditional instrumental play/performance practice); third-order surrogacy (imagined gestures and questionable reality of the source or cause); and remote surrogacy (source and cause are unknown, and human gestural origin is absent) (SMALLEY, Denis, "Spectromorphology: Explaining Sound-Shapes", Organised Sound, vol. 2, n° 2, 1997, p. 111-112).

[5] The configuration of chained structural functions varies, but for clarity, the generalised description of attack-decay-upbeat will be used in this discussion when referring to this composite of sound material.

[6] SMALLEY, Denis, op. cit., p. 117-118.

[7] LEWIS, Andrew, op. cit., p. 73.